The Mission: Impossible movies are not overly concerned with race. Not to say that this franchise only stars white people.

Ving Rhames’ Luther Stickell is there from the start, Mission: Impossible (1996). Thandiwe Newton is Ethan Hunt’s love interest, the professional thief Nyah Nordoff-Hall, in Mission: Impossible 2 (2000). Maggie Q, of Vietnamese descent, is IMF agent Zhen Lei and Laurence Fishburne is IMF Director Theodore Brassel in Mission: Impossible III (2006). Paula Patton, whose father is African-American and mother is white, is IMF Agent Jane Carter in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011). Angela Bassett is the tough-as-nails CIA Director Erika Sloane who joins the cast in Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018). And, finally, Pom Klementieff, French with a Korean mother, is in Dead Reckoning Parts One and Two (2024) as the assassin Paris.

The series just doesn’t treat people of color as anything but racially invisible. Well, except for in Mission: Impossible III.

Race is not foregrounded but is always there as subtext, embodied by Rhames’ Luther. Luther is a hacker and electronics expert. When the first movie was in production, as Rhames told BuzzFeed in 2015, there was certainly an idea of what a tech geek should look like. Though Rhames doesn’t spell it out, he likely meant stereotypes that presented in such instances as Matthew Broderick in WarGames (1983) and the Lone Gunmen, who first appeared in “E.B.E.,” the February 18, 1994 episode of The X-Files. Disheveled, physically not imposing and white.

Although Rhames has a point, he doesn’t seem to know that hacker clichés were already being subverted a year before Mission: Impossible. Two movies came out in 1995 that featured Black computer whizzes.

In Hackers, Laurence Mason plays Paul Cook aka “Lord Nikon,” sporting dreadlocks and a photographic memory. Johnny Mnemonic has Ice-T as J-Bone, rebel leader of the Lo-Teks. But while those movies are very cyberpunk, both figuratively and literally, and futuristic, Mission: Impossible strives to be more grounded and reflective of reality — a reality that thinks hackers are nerdy white guys.

Rhames also seems unaware of the likelihood of Luther being based on Barney Collier from the original Mission: Impossible television series (1966–1973). Played by Greg Morris, Barney was usually the builder and executor of specialized gadgets that the IMF teams used in missions. The President of Collier Electronics, a civilian contractor for NASA, Barney was notable at the time, much like Uhura on Star Trek, for being portrayed as an intelligent and successful Black character not defined by white stereotypes of his race. Morris’ son, Phil, even played Barney’s son, Grant, in a similar role as the tech expert on the 1988–1990 Mission: Impossible revival series.

So when Cruise handpicked Rhames after seeing Pulp Fiction (1994), director Brian De Palma seemed to have him in mind for the cyber-ops IMF agent, perhaps directly inspired by Barney Collier, who dies during the botched Prague mission. Rhames told BuzzFeed he had other ideas:

I remember saying to [director Brian De Palma], ‘Look, why is it that the black man dies 15 pages into the [script]?'” Rhames recently told BuzzFeed News in a phone interview. “I said that kind of jokingly, but it was the truth in many films. As a matter of fact, saying it nicely, [in] all these action movies, you are fortunate if there is one African-American or one woman. You know what I’m saying? So then they changed the script, and I lived.”

Instead, Emilio Estevez’s Jack was created to be one of the casualties and Rhames was slotted into the more substantial Luther role. At least, that’s my speculation on how the revision process might have gone.

Looking at the shooting script, by David Koepp and Robert Towne, the descriptions of Jack and Luther are relatively interchangeable: The former is said to be “an athletic American in his late thirties” while the latter is a “muscular, soft-spoken American in his mid-thirties.” Essentially the casting of Rhames was “colorblind,” with only the actor’s suggestion making for a bold, if implicit, step in overcoming backwards ideas about Black men.

The colorblind casting continued into Mission: Impossible 2. Nyah isn’t described at all in Robert Towne’s 12/4/99 draft. Apparently Newton had already known Tom Cruise and his then-wife Nicole Kidman, having worked with her in Flirting (1991) and him in Interview with the Vampire (1994). They wanted her for the role.

What stands out about Newton is she is one of the few women-of-color leading ladies in Cruise’s filmography. She is part of a very exclusive club that only includes Cordelia Gonzalez as Maria Elena — a sex worker Cruise’s Ron Kovics falls for, albeit briefly — in Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and Penélope Cruz as Sofia in Vanilla Sky (2001), a role she reprised from the original 1997 Spanish film Abres los ojos (Open Your Eyes).

Every subsequent Mission: Impossible movie feels like a self-aware course-correction of the aberration that is Nyah Nordoff-Hall’s wild, sexy, “exotic” nature. The third movie introduces Michelle Monaghan’s Julia, a girl-next-door domestic haven for a now-retired Ethan. Much has been said about how the marriage to Julia mirrors Cruise’s real-life courting of Katie Holmes at the time and how Monaghan does look similar to Holmes. Applying that same psychoanalysis to the cipher that is Ethan Hunt, you might read his attraction to Julia as unconsciously recreating his dynamic with Claire Phelps (Emmanuelle Béart) from the first movie.

Claire was the wife of Jim (John Voight), and forbidden fruit. The brown-haired Julia not only resembles Claire but is unattainable in her own way. Ethan has to leave her as his lifestyle will always put her in danger.

She’s also his excuse to stay chaste around more, ahem, colorful women like Zhen and Jane for the rest of the series. Yet after Ethan has put Julia in hiding, the character with whom he’s truly shared a flirtatious spark — even if it’s stayed platonic through Fallout — is the white, dark-haired Ilsa Faust (Rebecca Ferguson). And the previews and press for Dead Reckoning certainly imply that Hayley Atwell’s Grace, a burglar who is reminiscent of Nyah in every way except skin color, is a new love interest for Ethan (not unlike how Atwell was rumored to have dated Cruise). Hitchcock had his blondes; Cruise has his brunettes.

Unfortunately, with romancing Ethan off the table, Zhen and Jane aren’t given much to do. Zhen is your standard badass and Jane is mostly defined by grief over her dead lover, IMF agent Hanaway (Josh Holloway).

What does set Zhen apart from Jane is she’s Chinese. And boy does the screenplay by Alex Kurtzman, Roberto Orci and director J.J. Abrams let us know. We’re told “Her street-primer was the Chinese triads,” something never mentioned in the finished movie. And the prayer she mumbles for Ethan when he’s breaking into the HengShan Lu Building is explicitly said to be Chinese. In the script she and Declan (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) repeat the prayer together but in the movie they’re cut off. One does wonder why you’d write a fierce Chinese character, send her to Shanghai…and then sideline her from most of the action.

But Abrams & co. did manage to explore race in the final cut, more than the filmmakers behind the other Mission: Impossible movies, with Fishburne’s Brassel. He is introduced dressing down Ethan and IMF Assistant Director John Musgrave (Billy Crudup) and is described as “Somewhere between Joe McCarthy and Wyatt Earp. Not in a good mood.” Bassett’s Erika Sloane is revealed with similar intimidating language in Fallout, as she is said to be “A formidably suited woman (40s) [who] walks with purpose.” Again, with both characters, no mention of race.

But he has a provocative bit of dialogue during this scene establishing his character. As he breaks down how arms dealer Owen Davian (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is so elusive as to be like an invisible man, Brassel looks at Musgrave and says, “Wells, not Ellison, in case you want to be cute again.”

Wells being in reference to H.G. Wells and his 1897 novel The Invisible Man about a man who scientifically renders himself invisible. Ellison being Ralph Ellison who wrote 1952’s Invisible Man about living as a Black man in America. Taken in isolation, Brassel’s comment could be viewed as defensive, but it’s aimed at Musgrave for a reason.

Musgrave is not just the traitor who has been sabotaging Ethan the whole movie, he’s a racist! Musgrave lays out his motivation while trying to figure out what a tortured Ethan knows:

I wasn’t gonna let Brassel, of all people, undo the work I’d done. I took action, Ethan, on behalf of the working families of our country. The Armed Forces, the White House. I’d had enough of Brassel and his sanctimony. IMF Executive Director. He’s an Affirmative Action poster boy.

The implication is that all the staples of America are everything Brassel is not. Which must mean Brassel was un-American, a charged accusation during the height of the War on Terror.

The rant becomes even more rancid when considering the June 2023 overturning of Grutter v. Bollinger by Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. That original Supreme Court case ruled in 2003 that minorities could be shown preferential treatment in college admissions. I don’t doubt the screenwriters, and in particular Orci, had those recent headlines in mind when working on Mission: Impossible III.

Orci, who was born in Mexico City to a Mexican father and Cuban mother and moved to the United States when he was 10, has never shied away from racial and political issues. A decade ago he was a notorious 9/11 Truther on social media before deleting his Twitter in a huff. As I’ve written about before, he clearly wove those ideas into the screenplay for Star Trek into Darkness (2013).

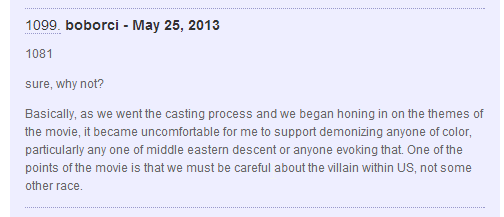

Orci not only positions a false flag operation as a major plot point in that movie, but also tries to parse out a theme by changing the character of Khan to a white man. Everyone knows Khan, on the Star Trek episode “Space Seed” and in the movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), was a POC — an Indian played by Ricardo Montalbán, a Mexican actor. However, the modern Khan was played by Benedict Cumberbatch, for reasons Orci explained on Tumblr:

Not coincidentally, Mission: Impossible III also ultimately pivots around a false flag. Musgrave’s Machiavellian plan for collaborating with the enemy is so Davian will deliver a Weapon of Mass Destruction to a Middle Eastern buyer. Musgrave will then have cause to preemptively launch a military strike. As he coolly clarifies: “And when the sand settles, our country will do what it does best. Clean up. Infrastructure. Democracy wins.”

The moral would seem to be clear. Brassel, who at one point proclaims to Ethan, “I will bleed on the flag to make sure the stripes stay red,” is the real American patriot. Musgrave is just another corrupt white bureaucrat. Case closed.

Wait, the movie isn’t over yet!

Ethan, the gallant hero, and Brassel share one last peculiar scene together. The IMF Executive Director is apologizing, hands Ethan an envelope and says, “Call it reparations for anything I might have put you through.”

Reparations. A term that can simply mean paying someone back for an injury, but in contemporary times has come to be associated with reparations for slavery. In fact, the first National Reparations Convention was held in Chicago in February 2001, so the concept would have been in the news.

What could Orci, Kurtzman and Abrams possibly mean by putting this line in the mouth of a Black man? The letter in the envelope is implied to be a job offer, so while you might infer Ethan is being offered Musgrave’s old position, Brassel’s near-groveling almost hints that the grinning Cruise avatar will take over as boss.

What a strange note to end the movie on. I can only conclude that the Mission: Impossible movies are better off not trying to say anything about race, and that Orci is likely the one to blame for the muddied, mixed messaging.